China is currently at a crucial juncture in its economic history: Martin Wolf

Compared with Japan in 1990s, China's economic growth potential is substantially greater. So, with the right policies, China should not end up like Japan, renowned British economist Martin Wolf, associate editor, and chief economics commentator at the Financial Times, told the Global Times in Beijing.

He suggested that China should reduce the national savings rate and stimulate consumption. And a key lesson is not to "allow deflation to set in," otherwise monetary policy will become very ineffective. If this happens, policymakers will be forced to use fiscal policies massively, which is very expensive.

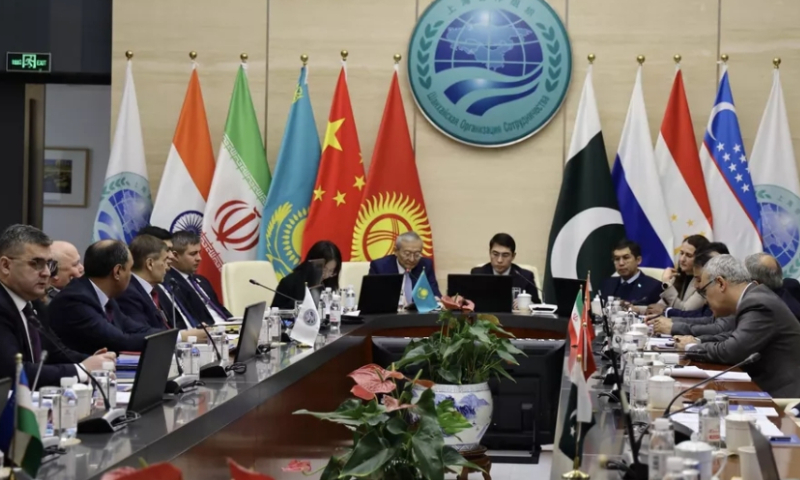

Wolf made the remarks in an interview with the Global Times on the sidelines of a seminar on Globalization and the Chinese Economy organized by the think tank Center for China and Globalization (CCG).

"Today is a moment in Chinese economic history that may be quite important for the next 10 or 20 years," he said.

"China is, relatively speaking, much further from high-income status than Japan was in 1990. So its growth potential is substantially greater. There is much less reason for the productivity slowdown that occurred in Japan. In that sense, with the right policies, China should not end up like Japan," Wolf told the Global Times.

He pointed out that the similarity between Japan and China in history is that they both have very high savings rates. The saving rate stood at about 40 percent of its GDP at its peak in Japan. This is great for a rapidly developing manufacturing country building a modern economy from scratch, as these savings can be converted into investments when it grows at 10 percent.

However, when Japan became a high-income country and caught up with most of Europe, its savings rate still accounted for 35 percent of GDP, but the investment rate declined and the account surplus exploded.

At that time, Japan did not make the wise decision to reduce the savings rate in a timely fashion, but instead decided to expand domestic investment, aggressively lower interest rates, and expand credit, leading to Japan experiencing the largest real estate boom in world history, reaching its peak in 1990. However, this economic bubble burst in the 1990s. When the economic bubble collapsed, the Japanese government did not implement effective artificial stimulus, nor did it change the macroeconomic structure in the early 1990s, leading to deflation.

"This is the lesson from Japan's experience," Wolf told the Global Times.

"Do not allow deflation to set in. It's very important not to let it because then you've got falling prices. If you've got expectations of falling prices, monetary policy becomes very ineffective. You then are forced to use fiscal policies massively, which is very expensive," he said.

The British economist believes that a key goal of China's macroeconomic policy is to transform the country into a full, all-around, and high-income nation. Despite facing more challenges at present, this goal is still achievable.

He argues that in order to achieve this goal, an important task is to improve underlying productivity, namely Total Factor Productivity (TFP). TFP is an indicator that measures the ratio of total output to all factor inputs.

In recent years, China's total factor productivity has not been growing rapidly, mainly due to the country's previous high investment rates. However, in recent years, the investment rate has been slowing down, mainly due to declining profits and instances of "overinvestment" in some regions in previous years.

Wolf told the Global Times that China can seek new large-scale domestic investment projects that are efficient and productive, absorbing resources and savings that cannot currently be effectively absorbed. "In my view, the most plausible large-scale investment that is already happening is various forms of renewable energy."

He noted that China can also increase investment in manufacturing. However, it is important to be aware that investing in manufacturing may lead to overcapacity. If this excess capacity is exported to Europe or the US, it will face fierce resistance. At the same time, other developing markets are not that big and have a limit.

In the field of investment, He said that two issues need to be emphasized. First, as most of China's infrastructure has already been built, real estate will no longer play a significant role in investment.

Second, it is important to produce good "valuable GDP," which means generating GDP that actually benefits the current or future welfare of the Chinese people, rather than creating things that will never be used in reality.

The creation of useless GDP should be avoided, he warned. For instance, if you build vast numbers of tower blocks which are not occupied, that is not productive GDP," he said.

Compared with investment, the more important thing is to drive up consumption, he stressed to the Global Times.

Currently, China's national savings rate is the highest in the history of the world for a country at this level of development and size, comparably.

"The national savings rate is too high to be productively absorbed in the economy at current levels of GDP. There is no plausible investment with one exception which can offset that. And the last one that did absorb a lot of these savings is this huge real estate building boom. But that's pretty clearly coming to an end," he told the Global Times.

Therefore, there is an urgency to boost consumption. "Consumption has to rise and the drivers [for economic growth] will be consumption because that's what they've been for every country that got to the sort of level of GDP that China has now. The question is only how it's done."

According to him, the consumption could be public consumption or private consumption. Public consumption, it means taxation, while for the private consumption, it means some combination of lower household savings and redistribution of income.

"This is going to be fantastically difficult," he said, adding that driving consumptions can be done in many different ways.

When discussing globalization and China's role in the world economy, Wolf believes that the fundamental driving forces of the process of global economic integration over the last two centuries have been the resource and cost advantages, transportation and communication technology innovations, and policy and political openness.

In recent years, the vitality of these driving factors has weakened, leading to a slowdown in globalization. However, the end of the "hyper-globalization" era does not mean the end of globalization. Despite facing pressures from economic adjustment costs and tensions among major powers, the momentum of globalization remains strong.

In recent years, Western companies have increasingly focused on political risks and sought to diversify supply chains for hedging purposes, but this does not mean de-globalization. The current issue lies in whether a framework of trust and cooperation can be established, for which both China and the West must work very hard, he noted.